You’d never know that there was a Ford Ka roof panel where the Webasto used to be.

Or that the owner who restored this Jaguar E-type was learning all the way.

A solid grounding in engineering – his company made irrigation systems – and a previous life as a mechanic with the McLaren Formula One team helped.

That was back in the day when F1 spanner men were jacks of all trades who could tackle everything and a team of only six looked after two cars.

Steve Bunn bought the S1 4.2 as a driver-quality car in 2001 – and then quickly found that it wasn’t as nice as he’d thought, especially under the skin: “The sills were in two pieces, for example, and it was metallic black, which Jaguar never offered.”

When he sold his business in 2006 and retired, the E-type went into storage: “But I knew that I was going to have to restore it.”

The process started in 2010 and, inevitably, the rot was worse than it first appeared.

A lot of new metal was needed, including floors, rear quarters, inner rear arches, one complete rear wing and half of the other.

It also needed both outer sills, one inner plus the strengthening pieces inside – and that roof infill to return the coupé to its pure teardrop shape

“I’d been driving along and realised that all cars have a compound curve in the roof, so it was just a case of measuring up the size of patch that I needed and then going around the scrapyards until I found something that matched.

“I was quite pleased that a Ka fitted the bill because at the time Ford owned Jaguar.”

The panel was joddled then held in with 50 or 60 spotwelds, in two rows to reduce distortion: “Luckily I could reach in through the windows with the welder.”

“People have said ‘you know that it’s the hardest car to restore,’ but it’s what I had, and it didn’t occur to me that I couldn’t do it,” he says.

“That said, once I got the body back from stripping I thought I’d better do that first in case I couldn’t manage it.

“It was tempting to do some of the easy stuff first, though, such as rebuilding the rear axle.

“When I went to collect the shell, the firm that had stripped it said: ‘Don’t be alarmed by what you’re left with. We’ve seen worse.’”

“They did also let on, though, that some customers are so dismayed that they ask them to scrap what’s left after dipping,” explains Bunn.

Removing the paint, filler and rot uncovered a multitude of older repairs, so it was out with the grinder and snips.

A home-made rotisserie helped – aka one scaffold tube and two welded angle-iron tripods

Bunn also welded bracing inside the door shuts to hold the structure straight while the sills and rear quarters were off. Not all at the same time, of course.

The new panels were fitted up, then held in place with aircraft-style fasteners while he welded them on.

He says: “The panels came from Martin Robey, and most of the other bits I got from SNG Barratt – largely because their website was the easiest to navigate.”

“The hardest bit was getting the gaps right,” adds Bunn. “I wanted it all metal, not filler.

“I was lucky with one door, but the other was a bit tight so I had to unfold it and try again – luckily the metal didn’t split, and because it needed to be smaller it didn’t leave a ripple in the skin.

“I did end up with a bit of filler in it, though.

“They were leaded originally and I tried using that, but couldn’t get on with it.”

To support the body during the build, and to transport it to the paint shop, Bunn made a pair of dollies – one for the main shell and one for the front-end panels: “To paint the underside of the bonnet, it was bolted to the dolly to allow it to hinge up as it does on the car.

“The body was transferred to the rotating jig once it was at the paint shop, to allow access to all areas.”

All of the machining work was contracted out, but Bunn rebuilt the engine at home.

An electric fan is the only deviation from standard spec, although the wishbones are nickel-plated – since E-types were being built, cadmium has been outlawed by the ’elf an’ safety brigade.

Bunn did the electrics himself, with the help of a wiring diagram and a multimeter.

“The interior was made by MCT Jaguar Restorations in Nuneaton, including recovering the seats,” he says.

“I fitted it all, including the headlining – which I had to do three times. They only just fit and the first time there was a small gap at the back.

“The second time there was still a little gap at the back, but on the third it was just right. Each time you repeat it means a day on your back, scraping off all the old glue.”

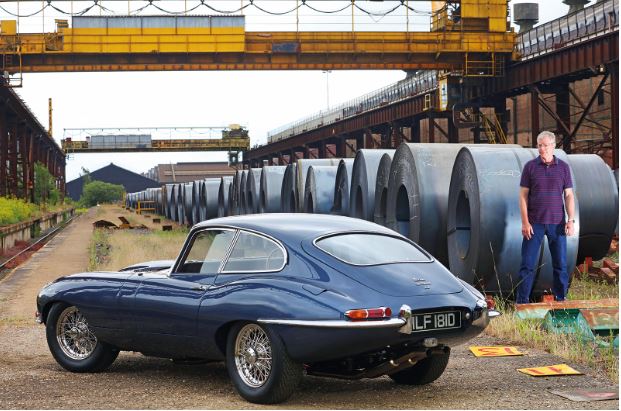

The paintwork was by Dean Aldridge at Shire Lodge Autos in Corby, and the front subframe is correctly finished in body colour: “It was originally light opalescent blue but I saw an Eagle E-type in this shade with a red interior.

“I called the sprayer and said: ‘Don’t order any paint yet!’”

It was the right call – the Malcolm Sayer-inspired shape looks gorgeous in this dark blue.

The body is dead straight, with profiles and contours lining up, witnessed by the consistent reflection lines.